overview

overview

A film adaptation of Marek Hłaska’s novel „Następny do raju". Stefan Zabawa is sent to „the depot of the dead”, a unit which transports wood and is practically closed off from the rest of the world. It consists of criminals who work in dangerous conditions to avoid a sentence. Zabawa starts to work with a difficult group of employees, among whom any unadvised gesture may lead to conflict…

storyline

storyline

It is 1946. Winter. On the doors of the service station there are still old posters asking to vote ‘three times yes’. Stefan Zabawa goes inside. He tells the mechanics that they must fix his truck until morning. He is angry – he has gone to ask for new cars, but didn’t manage to get them. The mechanics are fixing a few trucks used by KBW the previous night in a fight with forest gangs.

Zabawa also goes to the director of the garages. There he is commanded to go to the ‘depot of the dead’ and get a job there. The director warns him that criminals who want to avoid their sentences work there. The base is almost completely cut off from the world. You can only get there with an adequate truck. Zabawa does not agree to go there at first, but the director tells him that it should be an issue of honour for him. He gives his subordinate a gun “so that he doesn’t get killed somewhere in the mountains”.

Zabawa doesn’t say much, but you can tell he has been through a lot in recent years. He must have thought that now he would be able to live more calmly. His expedition to the base is a step in his necessary fight. Zabawa believes in the new reality, he is ready for sacrifices. On his way to the base he meets Nr Nine, Warsaw Man and Orsaczek – people from the base. They were right in the middle of loading their friend’s body into a wooden case – he skidded off the edge of a cliff. They are cold and angry. They are tired of the job and of driving the trucks which could break down any second. They agree that the next day – no matter what happens – they will go back to the city. Zabawa tells them that they must day because there is no one to carry wood which is needed in the city. He leaves no doubt that there will be no new cars. Warsaw Man and Nr Nine realise right away that Zabawa has been sent by the management to control them. They begin to call him a communist between themselves. They go to the base together. Warsaw Man decides to finish off Zabawa, who is driving behind them, right away. On the turn, when changing the direction, he turns his headlight around and tries to blind Zabawa so that he does not notice the edge of the cliff. Zabawa turns in the last moment. The wheels of his car barely stay on the road. The Warsaw Man is devastated.

Apostle, another driver, is waiting for them in the base. He is an interesting person, religious, good-hearted, and – as he has himself – preserved by alcohol. He is sad because of the death of their friend – he seems to be the only one who really cares. Zabawa unloads his luggage from the truck. Warsaw Man and Nr Nine stand there astonished, because they see that a woman gets out of the cab. She is introduced as Zabawa’s wife. Soon the base is joined by Guerilla. He was encouraged to join by Zabawa. Guerilla wanted to become an aviator or sailor after the war, but he didn’t get a job anywhere. He had no other choice but to go to the base – he had to make a living in some way. Warsaw Man goes outside to meet him. He gets angry right away that Guerilla is smoking by the barrels of gasoline. Guerilla doesn’t care and even – in order to make an impression on the Warsaw Man – spills a bit of gasoline from the barrel and sets it on fire. Warsaw Man runs up with a blanket and puts out the fire. They begin to talk. That’s when Warsaw Man says that he is working in the base because he is in danger of jail. Nr Nine is most likely an ex-doctor who killed his wife in unknown circumstances. Almost nothing is known about Orsaczek.

The men do not give up on their plan to go to the city the next day. They decide to play poker on the last evening. They do not want to listen to Zabawa, who has that they must stay. Zabawa plays with them. During the night he whispers to his wife Wanda to go outside with him. The woman thinks it’s about love, but Zabawa actually just needs her help with disassembling carburetors by Nr Nine’s, Warsaw Man’s and Orsaczek’s trucks. That is the only way he can make them stay.

In the morning when they realise what Zabawa has done they want to beat him up. That’s when Zabawa takes out his gun. Warsaw Man want to lunge at him anyway and says that he does not have enough bullets to kill them all. Zabawa shoots out his whole magazine. It turns out that he would have had enough bullets. Although he is now vulnerable, the men do not feel like beating him up anymore. They decide to go to the city on foot. They must go a long way, but do it anyway. Orsaczek plays on his accordion, everyone sings „Harmonia z cicha na trzy czwarte rżnie...”. At first they are joyful, but they can’t stop thinking that if Zabawa fixes their cars he will take credit for how they cared for their trucks for many months. They decide to go back. They would rather fix the trucks themselves and make a loud entry to the city in their cars.

In the evening Zabawa encourages them to play another round of poker. They don’t know that the game is played with denoted cards. When Zabawa wins all of their money, the next days of their work in the base are the bid. They must stay. Only Warsaw Man realises that Zabawa was deceiving them.

Zabawa’s wife, Wanda, begins to seduce Nr Nine. She believes that the man will take her back to the city. Nr Nine starts sleeping with Wanda. One day he decides to go for wood one last time, return to the base before the others and take Wanda to the city permanently. During the chopping an inspector from the management stops him. He wants to go along with Nr Nine. Nine must go very low because just before him Orsaczek is taking a false course. Orsaczek does this to save up for a taxi.

Nr Nine’s brake hasn’t been working well for some time. Only the hand brake works. He arranges with the inspector that if something happens he will jump to the side. On one of the serpentines Nr Nine sees a division of soldiers going down the road. Because of the gale he does not hear the beeping of a truck riding down the road. The hand brake stays in Nr Nine’s hands. He has only two choices: to run into the group of soldiers or ride off the edge of the cliff and die. The inspector begs him to go straight, but Nr Nine turns. They both die.

It seems that this is the end of Wanda’s dreams of going back to the city. However the woman starts to seduce Guerilla. The only thing she cares about is a chance to get out of this place. However it doesn’t work out with Guerilla. On one of the expeditions for wood he goes first. The whole column stops in front of a swampy turn wondering what to do so that everyone can get through. Guerilla, without listening to anyone – thinking that he will get through – rides straight into the mud and obstructs the road. He is afraid of everyone’s anger and runs away.

Wanda’s next lover is Mouth, who brings the drivers their payments on his motorcycle. Mouth uses her cynically – he never even intends to take her with him – and he is beaten up for this by Warsaw Man.

One day Apostle loses his logs from the truck. Using a pry, he tries to drag them in. Zabawa drives up. Now he is standing by the pry, while Apostle drags the logs on a rope. Suddenly Zabawa doesn’t have enough strength and lets go and the logs fall on Apostle, who dies in agony. Orsaczek finds out that the money he had been saving was never enough for a taxi and is in a rage.

The final scene shows Zabawa and Warsaw Man – until now enemies – sitting together in front of the base. They tell each other their real names. In the background there are sounds of engines – new trucks are coming to the base.

comment

comment

press review

press review

In the film, very much loyal to its literary origin, the image substituted the word, and the word became and additional to the live image. And here we see the philosophical, psychological, intellectual weakness of the literary prototype. No hidden agenda, no subtext. Denuded from its creative role, the words and images are flat, people are puppets, the audience cannot add their subjective text to the image, although they used to add an image to the words. This is definitely not fault of the actors. All of them are wonderful and usually their acting saves the film, while where they are unbearable (the insistent face play of Karewicz during the poker game) – the director is responsible, just as in the unnecessary and cheap counterpoints (money blown around by wind). The director is also responsible for Wanda’s silly looking ‘home’ obsession, for everything, which was supposed to be tragic, but turned into comic and made the audience laugh contrary to what the authors intended. Finally, the director’s fault is people asking after the screening: what happened to Guerilla, where did Orsaczek go? The director? Or maybe also the writer? Maybe this literature, fascinating with its naturalistic brutality, when translated into image loses its terror and cruelty in the grotesque caricature of the character and becomes silly. Maybe the anti-humanistic literary drawing copied onto the screen causes mockery and cheap laughter, because there was a lack of a deep psychological and ideological truth? In the literary story what fascinated was the impetus, the wide breath of the locations, the London severity, the sharpness of the characters, their extremity. Some of that remained in certain parts of the dialogues, in some gestures, in some landscapes (…). For two hours rain falls, snow from the first sequences turns into mud, this mud and bad weather are obsessive and also intrusive. Even Iżewska must make herself go with Mouth in the fog and drizzle. I don’t know what this was meant to do, but I know that it is extremely wearisome for the viewer (…) The fog has grown to the size of a symbol, so it has become unreal and in effect did not work (…). The film is in fact not an intellectual proposal, or a sensual one. It has no depth and no adventure. It strikes with artificiality of the social content and with dullness of the action. Good photography of K. Weber, good acting, leftovers of the Polish–London literary climate and the fact that as a whole it is gloomily muddy (…) may bring the film a foreign laurel.

Kazimierz Dębnicki, „Film”, 1959, nr 35

We are told that the location of the action is Bieszczady, and the time is 1948–1949 (here Toeplitz makes a mistake). In this time and place a group of convicts and deviants, so-called ‘finished people’ meet in order to curse their fate and face a mortal battle with winter, mountains and broken-down trucks. Their dream is to run away from that cursed place to a normal life, while at the same time the mountains which give them the circumstances, space, relative asylum for people on the edge of the law disable them from making that decision. That is why they die one by one, choosing death instead of running away. I know two places in the world where a similar situation would be possible (…). However neither of these would be in Bieszczady or anywhere in Poland. That is because in Poland there are no such long distances and impassable tracks which would not allow one to go from any point – after walking one day maximum – to the closest city. There are also no such places where the law doesn’t reach, for the same reasons. (Pardon, there were such places, in Bieszczady in fact, but back when the UPA was there. However in ‘The Depot of the Dead’ nobody mentions UPA, only the space, snow and being cut off from the world). That is why the initial situation in ‘The Depot...’ is completely made up and impossible to me. The second element which raises questions are the characters in this film. The authors grouped together a terrifying gallery of types. Killing one’s own wife is the most delicate thing characters of this drama have done. I’m not saying that this kind of a crowd is impossible. However it seems hardly possible to me that these enterprising people would be the first to volunteer for a mortal battle for a wood industry plan and that they would be the best material for Zabawa’s, the party’s general secretary’s, educational activity. We do know that Makarenko did things like this, but first of all he had to do with young people, and second of all he could give his pupils better and more attractive perspectives that Zabawa could by proposing only a ‘manly death’. My God, a ‘manly death’! It is so sleek, romantic and childish in this ‘raw’ film! Some critics speak with delight about the scene from ‘The Depot…’ when the drunk workers bring their dead friend to the chapel and sing him a song instead of praying. How lovely and effective that is! Just show mi at least four Poles out of which not one knows the words of a prayer and I will believe that ‘The Depot of the Dead’ is a realistic film.

Krzysztof Teodor Toeplitz, „Świat”, 1959, nr 37

‘The Depot of the Dead’ is a successful film, and this fact in itself is worth analysing. The film is the place of a scuffle of two extreme tendencies, counteracting each other as it is usually thought, excluding one another – ‘black’ and ‘socialist realism’. In the meeting of the two – as everyone predicted – only a strange creation could emerge: that is why the success of ‘The Depot…’ is such a surprise which makes us re-thing the possibly too simple opinions about the antagonism which has been a large part of our culture in the last years.

Zygmunt Kałużyński, „Polityka”, 1959, nr 34

This would have been a ‘production’ film if it weren’t for the fact that the main characters have a negative attitude towards reality. That is a significant difference. That is where the violent and open conflicts between people from the base come from, as well as those between them and what the so-called ‘company’ represents. The main characters are not sacrificing their lives for any ideology. These are people who are focused only on their own business and with no empathy. That is why the conflict with the company is open and fierce. This film breaks the myth of the necessity of obedience and subordination, it is a brutal insult for sacrifice and blind heroism. Zabawa with a gun in his hand stopping the men from leaving the base of drivers and Zabawa, who stays until the very end – that is surely the main character of Wajda’s ‘Kanał’ going for his death to the place where he does not expect to find his plutonium. The tragedy of his heroism is so much greater because he does not believe in its necessity anymore. He stays in the base because he has no other choice. However that base has taken away everything he had to lose. The film has no philosophy. The film does not postulate, it doesn’t even stand in the defence of humans. It is a vulgar negation. However it is not a negation of nonsense, requirements impossible to meet, cruelty in the name of humanism. The film, with its script written by the director Czesław Petelski is very different from the methods used by contemporary Polish filmmakers. It is completely free of a metaphorical convention in saying what the author wanted to say. The result of the attention to detail is definitely a great gallery of types and faces. These are real people and great actors. Fogiel as the Apostle creates a great figure. The cast for Zabawa’s role is a bit of a mistake. Zygmunt Kęstowicz is certainly a good actor, but he is not the type which fits into the character in the script. It seems that the script was the most precious part of this film. It is the script, not the directing, which imposes the atmosphere. There are a few excellent scenes in ‘The Depot…’ (like the scene in the Church when Orsaczek plays on the pipe organs), but there are some scenes which are not good, which are banal. One of them is of course the final scene, with pathetic acting, which leaves behind bad memories after leaving the cinema. It’s a pity, because the film is worth a lot.

Wojciech Solarz, „Film”, 1959, nr 35

I think that in the figures of Zabawa, Warsaw Man, and probably also Nr Nine the humanistic idea of the film is visible – the belief in humans. Believe – often – above all. Surely every viewer will see this film differently. Someone who knows the first days of building, the first struggles and problems, will see a lot of his recent life in the film, even though the action of the film and its conflicts were very piled up. The compiled past of most of the characters condenses the tensions and events. The large psychological richness in the main characters of the film (for example Warsaw Man) are worth noting. They are original, rich in conflict (let’s compare, for example, Nr Nine’s past and the circumstances of his death, of Zabawa’s personal drama). The actors used this chance excellently. It would be difficult to distinguish one among them. I personally like Emil Karewicz (the Warsaw Man) the most – maybe because it was an interesting character (…). Teresa Iżewska as Wanda is very interesting also, much more so that in the ‘Rancho Texas’ or even ‘Kanał’. Apart from a few posturing texts in the dialogue it is realized without a single error. Compact, dense, dramatic action, lots of great scenes (…), wonderful photographs of Kurt Weber, which accurately used the snowy and muddy scenery. Director Czesław Petelski deserves appreciation for this film – consequently realistic, touching, but luckily not naturalistic in style.

Stanisław Janicki, „Żołnierz Wolności”, 1959

did you know?

did you know?

The film was applied for the festival in Mar del Plata (1960) and took part in a retrospective of Polish films in Oberhausen (1963).

For the scene in which Nr Nine falls off the edge of a cliff a puppet with Leon Niemczyk’s face and body was made.

In the book ‘The private history of Polish cinema’ Ewa Petelska – Czesław Petelski’s wife – says that although her name is not in the credits she made most of the atelier scenes.

The title ‘The Depot of the Dead’ was the idea of Roman Bratny, the director of the literary team Studio.

The company bought desolated trucks especially for the film.

There were 88 shooting days: 30 in an atelier and 58 on location. The latter were done in Lądek-Zdrój, in Wrocław and in Góry Bielskie.

Hłasko worked in the transport base Centrala Drzewna in Bystrzyca Kłodzka in 1950.

Andrzej Wajda was the first to propose Hłasko to write a script about drivers from the transport base. Together they wrote a text titled ‘The big bluff’ (later calling it ‘Stupid people believe in the morning’). Wajda even begin to find the cast. However Hłasko, without consulting Wajda, sold the script to the Studio team run by Aleksander Ford. Wajda had some bad experience with Ford when working on his debut, so he backed out of the project. Czesław Petelski took over the script.

In April 1959 the „Zielonogórska Newspaper” wrote that the director of the WFF in Wrocław was angry at the makers of ‘The Depot…’ that they put themselves in danger while making the film. The drivers and actors would ride in cars with open doors to jump out in case they skid in the mountains.

In the scene of Nr Nine’s death in which the logs fall off his truck there is a short break in the image. This is because Kurt Weber – as his said himself during the festival in Cieszyn – made this scene with a hand camera and his finger moved away from the button for a second.

In the original version Guerilla played by Tadeusz Łomnicki was not included. As Wanda Wertenstein suggests in an article in “Kino” (nr 10, 1979), Hłasko and Petelski may have wanted (although this is only a hypothesis) to have an ironic settling of accounts with Lutek from ‘Piątka z ulicy Barskiej’ or Stach from ‘Pokolenie’, which Łomnicki played. This may also be a converted theme from the first version of the story about drivers from ‘Baza Sokołowska’.

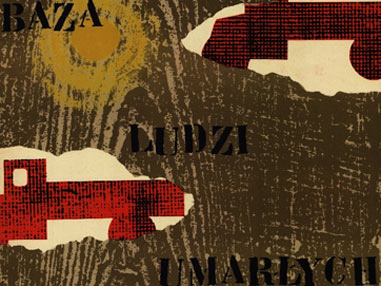

posters and stills

posters and stills

In the photo: Leon Niemczyk

In the photo: Emil Karewicz

In the photo: Roman Kłosowski

In the photo: Teresa Iżewska

In the photo: Zygmunt Kęstowicz

At the end of the 50s Hłasko was one of the most sought-after writers in the film environment. Three films were made on the basis of his stories: “Pętla” by Has and “Ósmy dzień tygodnia” by Ford. Wajda also planned to work with Hłasko, they even wrote a script together, which became the basis for Petelski’s future film ‘The Depot of the Dead’. When Wajda found out that the film was to be made in the Studio team run by Ford, he backed out of the project. In June 1957 it was clear that Czesław Petelski would be the one to make the film – the script was approved and Hłasko was satisfied with working with the director. What is interesting however is that during the proceedings of the Script Board Aleksander Ford, whose team had bought the script, was against the realization of ‘The Depot…’. It was headed for production mostly thanks to Leonard Borkowicz’s vote. In ‘The Depot’ production elements were not missing – the wood was the most important! – but that was only a pretext. The film showed – as Wanda Wertenstein wrote – “what happens with people left to themselves, along in an outpost lost somewhere in the mountains”. The hopelessness of these people’s fate was dominant. They lived from day to day with no perspectives. Even if for a moment there was a chance for any of them to escape, they would die – like Nr Nine – in the mountains or they would realise – like Orsaczek – that there hope was useless. Warsaw Man was quite a different character. He had a completely passive attitude. Apart from talking about returning to the city every once in a while, he didn’t really care about anything. He is the one who stays in the base when Guerilla and Orsaczek run away. In fact the way the scriptwriters showed the fate of the two latter characters could be criticized. Guerilla’s fear and runaway do not interact with his previous heroic actions during the war. Unless we believe – although we can only suspect this – that Guerilla was in reality a mythomaniac who tried to show himself as a tough man but became scared when he actually met such people. On the other hand Orsaczek disappears from the screen imperceptibly. This character seems to be unfinished. At the moment of the premiere the problem was also that – although with time this seems intriguing– that the only positive character paled by comparison to others, at least until he became similar to the rest of the drivers.

The criminals from the base seem to be fascinating due to the mystery – we do not know anything about their fate from before they came here. At first glance they seem to be equally degenerated and rude, but gradually they show signs that some of them could have been doctors, intellectuals, scientists… Famous actors played in ‘The Depot…’. During screen tests - as Leon Niemczyk recalls – it was not Petelski who made decisions about the cast, but Hłasko. In the end he withdrew his name from the credits and there is no sign of who is the script author. The reason for this was the censor’s interference which Petelski had to deal with after the film was finished. For example he was ordered to shoot an additional scene with a conversation between Zabawa and the garage director in which the ideological goal of the expedition would be precisely known. However the most important issue was changing the ending. Hłasko wanted it to not leave any hope. Petelski however wrote a scene in which new trucks come to the base. This change was actually the direct reason why Hłasko backed out of the whole project. ‘The Depot…’ stayed on the shelves for a long time anyway. Ford, the director of the Studio team, stopped it. Because a lot was said about the film in that environment and everybody wanted to see it, Ford even sealed a copy in the assembly room. However the moment he left Warsaw, a final inspection of the film was quickly organized. Ewa Petelska remembers that the initiative came from Dylewicz. That’s when the film was distributed – in August 1959. Opinions about it were extreme, but with time everyone began to talk about it with admiration and it is popular among viewers until today. It is worth going back to the final scenes again. In the final version it gives the whole story a minimal optimistic tone. This was in a way a breakthrough of the fatalism of the Polish Film School. “In ‘The Depot…’ – as Stanisław Ozimek wrote in “The History of Polish film” – we see a victory with a high price, not quite certain and lacking a declarative literality. This feature in Petelski’s film was then bold and even pioneer”.