overview

overview

Tolek is the leader of a group of hooligans, Roman is one of the group’s members. They are both involved in the beating up of a man who may lose his sight. Because of a misunderstanding, Roman is taken for a hero who had saved the man. Basia, a journalist, becomes interested in the story and while she gathers information for her article she begins to have feelings for Roman. Roman is publicly called a hero, however he knows that he may lose everything when the victim regains his sight. Tolek and his group are also afraid of their victim getting better. They plan a mystification...

storyline

storyline

Warsaw. A group of five hooligans provokes people walking by the stairs next to Plac Zamkowy. Their leader, Tolek, insults a man in front of his girlfriend, saying that if someone would offend him like that in front of a woman, he would have beat him up. However the man walks away. Then the hooligans feel up girls by the CDT, stir up a fight in the Praga bar and another one on the street. Tolek is certain that everyone is afraid of him and takes advantage of this. However one of the group members, Roman, is very tired of Tolek’s dominance. They make a bet that if one day someone is stronger of more creative than Tolek, then Tolek will have to jump into the Vistula.

Late in the evening Tolek and his friends go to a closed funfair. They break in and put on the merry-go-round, then go into the mirror room. A fight breaks out because Tolek, in a flow of whimsy, tries to undress and make fun of Wacuś, the smallest of the group. His screams are heard by a random pedestrian who looks like a typical intellectual. He goes into the mirror room and tries to help Wacuś, but then the whole group throws themselves at him. The fight gets the attention of more pedestrians. The hooligans run away and only Roman remains, because he notices that he should run too late. He cannot get away from the intellectual, so he beats him to unconsciousness. However it is too late and people run over. Roman explains that he only wanted to help the attacked man and has nothing to do with the hooligans.

The injured man is taken to the hospital – he may lose his sight. All of the other witnesses are taken to the police station to give their statements. The sergeant believes that Roman really stood up for the victim. He is called a hero. A young journalist is present at the police station. She is looking for a good subject to write about and decides to write about Roman’s behaviour. Articles about the “young hero” appear in “Życie Warszawy” and “Express Wieczorny”.

The next day Tolek and his friends meets by the stairs again. They are impressed by Roman’s creativity and how he managed to get out of this. Tolek lost the competition, he must jump into the Vistula.

The young journalist, Basia, is increasingly interested in Roman. She does not know the truth, so she is impressed by his courage. She wants to write a detailed reportage about him. She visits him at home and finds out about his difficult family situation. His father is in jail for maladministration. He was most likely unfairly accused because of his old colleague who blamed everything on him. She is now taking care of Roman, probably because she felt guilty.

Basia takes Roman for a walk. The boy begins to pick her up. They fall in love with each other. However Roman is terrified of visiting the wounded man together in the hospital. He is afraid that the man will recognize him, but Basia does not give up. They go to the hospital and find out that the patient is feeling better. However he still has a band on his eyes, so he does not recognize Roman. However he will see again soon. He tells them that he works for the TV industry. He promises Roman to get him a job. Roman is terrified and knows that these are his last days of freedom. As soon as the injured man will regain his sight, he will see that Roman was the one who beat him up.

Tolek and his friends are also afraid, because the man also had seen them. They are angry at Roman that he agreed for his story to be in the papers and that he is in a relationship with the journalist, because this will cause them all to be caught. A fight breaks out. Roman decides to leave his girlfriend and run away to Zielona Góra. He does not take the offered job on TV.

Then comes the day when the wounded man will have his band taken off. However Tolek arranges a mystification. He decides to abduct him, supposedly in order to kill him. In reality he wants Roman to react. He knows that Roman will defend the man and gain the man’s respect.

comment

comment

press review

press review

„I have the impression that the director wanted to prove that many people who are casually called hooligans are not criminals, not enemies, but people who have been alienated from society, who have become lost in their understanding of the world, people who are overwhelmed by discrimination. In other words, they are like us, only lost (…). I also have the impression that Poręba wanted to say that the main reason for these people’s behaviour is a lack of interest from society, a lack of objective mental stimulus, independent of themselves, which would cause them to change their direction. Finally, boredom and a lack of ideology, an internal emptiness (…). When looking at it this way, the film seems to be amazingly optimistic. More optimistic than any other polish modern film. However does reality entitle us to believe so much in a person who has fallen so much to be a hooligan? Is this optimism really justified: if it’s so good than why is it so bad? I think that treating this too optimistically is the biggest drawback of the creators of this film”.

Andrzej Tylczyński, Zagubieni czy rozwydrzeni, "Tygodnik Demokratyczny”, 1960, nr 4

“The reportage observations of “Sleepwalkers” (…) are the most complex parts of the film and its greatest asset. Poręba and his cameraman, Tadeusz Wieżan, are great at showing the climate of the boys their minds, personalities, their moves and the lively image of the city. In this journalistic, not feature part of the film (this is how I classify the most important scene in the funfair), “Sleepwalkers” show their connection to the polish document. However, where the details and naturalism of the descriptions, the striving for noting the characteristic elements of this environment is substituted by a regular feature film, it becomes much worse. The intention of the authors was to make the main motive of “Sleepwalkers” the wonderful chance which opened up for one of the boys – Roman. (…) Roman, a mistake hero, and his story strikes with its superficial love story and bad acting. Because of its documentary-chronicle observations, the concreteness of the subject and materials, Poręba’s film (…) is – after finishing its settling of accounts with history – a position in polish cinema that prepares the ground for a new direction: research and interpretation of reality”.

Maria Oleksiewicz, Lunatycy, "Film”, 1960, nr 5

“Poręba’s characters are not just a group of young people named hooligans. They are the same boys who can spend an evening drinking lemonade in Stodoła or a bottle of beer in Manekin, which makes them even more dangerous for society, because they can change from nice boys in white shirts into murderers in an unnoticeable way, starting from ‘innocent’ behaviours like flipping over trash cans, swearing at people on the street, ‘games’ at the Funfair. They create a situation we can observe every day, while looking at it with understanding. We do not know that they can work like an organized group. (…) The asset of Poręba’s film is the truth of observation, a skilful psychological motivation of the characters’ behaviour, a documental exposure of the background. (…) The boys are full of fantasy when it comes to saving a friend in danger of getting revenge from the man regaining his health, a wounded engineer of Television Warsaw. Poręba’s characters, full of contempt for reality, try to defend themselves from any sign of sentimentality. At the same time they have a frightening lack of imagination. (…) Poręba’s debut is even more valuable, because the director was able to create believable situations without falsity and cheap declamation, situations which are fully justified and only the ending seems to be made up and reminds us of the climate of an adventure novel”.

Grzegorz Dubowski, Lunatycy – film młodych dla młodzieży, "Ekran”, 1960, nr 5

"The film begins in an interesting way by showing a group of juveniles who are dead bored, standing by the stairs, doing the strangest things out of boredom, things somewhere in between jokes and crimes, and finally committing a serious crime: beating up and crippling a man. After this effective introduction we expect a really insightful look at the psychological and social phenomenon of hooliganism, especially since one of the script writers of “Sleepwalkers” is a famous sociologist-“hooliganist”, Stanisław Manturzewski. Unfortunately this hope is soon destroyed and the film goes strongly in the direction of a moral story, similar in its climate to stories for ladies by Czarska or Zarzycka. (…) The script, even though it is banal, has some potential for bringing tension. Its primary element of action is the story of a man blinded by hooligans, who cannot recognize the man who beat him up, and this man pretends to be his defender. I think that the scenes with their conversations, the visits in the hospital, as well as the character of the vulnerable blind man could have been the basis for at least a few dramatic scenes. However Poręba consequently does not use these opportunities. He only gives a relation, scene by scene, in a very banal way”.

Krzysztof Teodor Toeplitz, Lunatycy, "Świat”, 1960, nr 6

“Finally a modern film! (…) However the creators (…) of it did not want to, as they said themselves, make a sociological treatise and showed hooliganism as a ‘biographical alley’ of a group of boys separated by a delicate border, as if of glass, from normal life. They showed all of this with a perfect sense of observation and a lot of knowledge about the environment (Poręba was once an incognito visitor in a reformatory house). The reportage style of narration made the image very natural, and its optimistic character was not tainted with moralizing. However this trust given to the viewer, especially a young one, may be dangerous. Among the young audience you could hear laughter and applause for the hooligans’ behaviours and authentic, loud prompting. Such misunderstandings in the receiving of the film were partly the fault of the realizers – I especially mean the speculative and illegible ending of the film, when the viewer has a hard time understanding Tolek’s motives. The leader of the gang, captivated by his friend Roman’s chance to go back to a normal life, wants to help him and stages a hooligan ‘abduction’ in order for Roman to be the hero. Of course it’s really bad when the ending of a film requires additional comments. (…) If, along with this, the director did not manage to show their longing for a life in accordance with society, he did manage to show this ‘sleepwalkers’ existence, dangerous balancing on the edge of crime, but on the other hand just as close to the possibility of awakening”.

Władysław Cybulski, Lunatycy, "Dziennik Polski”, 1960, nr 71

did you know?

did you know?

The premier of the film was in the "Pomorzanin” cinema in Bydgoszcz, where Bohdan Poręba comes from.

Zofia Marcinkowska was dubbed by another actress.

Marian Beczkowski was an amateur actor, he used to work as a Messenger in the Main Board of Cinematography.

The episodic roles were played by people from the popular cafe "Turystyczna”.

On the 26 of May 1959 in "Ekspress Wieczorny” there was an ad called “Extras needed for the film “Sleepwalkers”: “ We need extras for the film 'Sleepwalkers' – especially young people. Those interested may come to the directors of the film on 27 this month at 17.00 at Łazienkowska 6a at Torwar”.

Filming began on 4 May 1959 in an atelier in Łódź, the rest was filmed from 22 May in Warsaw.

At first Andrzej Mrozek was supposed to play Edek.

At the press screening of the film Ludwik Pak said that he was expecting the hooligans to speak unclearly and he tried to imitate this in order for the dialog to sound natural.

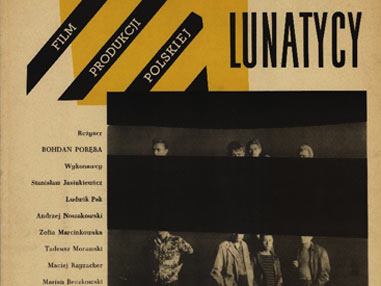

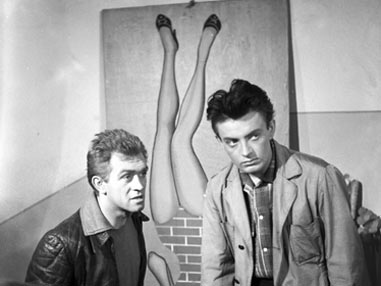

posters and stills

posters and stills

Behind the scenes. “Sleepwalkers” is an atypical position in Bohdan Poręba’s filmography. He is most of all known for his later films which show important moments of Polish history. In his debut Poręba used the rich experience he had from his documental work. That is why “Sleepwalkers” remind us of a feature reportage. “A film about young hooligans” – that is what the press wrote from behind the scenes about Poręba’s debut. The problem of hooliganism in the 50s was a very important topic of discussion. Hooliganism was a plague and it was impossible to remain silent about it and pretend it doesn’t exist. Documents quickly undertook the topic. There was a loud film “Caution, hooligans!” by Hoffman and Skórzewski in 1955. However viewers were waiting for a feature film about hooligans. There were previously two movies: “Piątka z ulicy Barskiej” and “Koniec nocy”, however the first one was about the past and the other was only available in a few copies. "Sleepwalkers” filled this gap. One of the script writers was Stanisław Manturzewski, a sociologist and specialist in hooliganism. In the script there are many episodes which were observed in real life – he explained. However the main idea of the film was not based on facts. It just shows a typical way of reacting in certain situations. Most of all we wanted to show the psychological atmosphere…

Hen, Ze St. Manturzewskim o "Lunatykach”, "Sztandar Młodych”, 1959, nr 125

Bohdan Poręba added: - It is important to us to show the reactions of these boys, especially Roman. It is extremely important for contacts and relations with this type of society and these types of groups. Personally I believe that we should not cross out even the worst of them. We must find a way to reach them, to find a common ground. It is worth doing this, because a lot can be changed. What and how – that is what interests me most.

J. Budkiewicz, "Lunatycy, "Głos Pracy”, 1959, nr 141

After some time it is visible, that the director’s idea made “Sleepwalkers” an intervention film. The image of the hooligans group is authentic as long as they are showed in well-known places in Warsaw: the Praga bar, CDT and the stairs by the rout W-Z. However as soon as the film tries to go deeper and explore the psyche of the main characters it is obvious that it is a situation made up at some desk, that it tries to impose too much of what “can be changed”. However these drawbacks seem smaller when you realise that it was a debut for everyone. It was a debut for Poręba, the script writers, Wojciech Kilar as the author of music and most of the actors. “I was involved in the film after eliminations. I am very happy that it was me who was chosen. I am a student of the Film and Theatre School in Łódź. I really liked the role, it is great and…difficult” – says Andrzej Nowakowski, who played Roman.

J. Troszczyński, Film o trudnej młodzieży, "Trybuna Mazowiecka”, 1959, nr 153

Zofia Marcinkowska said: Basia appeals to me with her character. She is joyful, scattered and emotional and she believes in herself. I am very happy that I can play her role. However my dream is yet another role. I would like to play a smart girl, but an ugly one, who has many issues with her appearance.

J. Budkiewicz, Lunatycy, „Głos Pracy”, 1959, nr 141

For Marcinkowska the role in "Sleepwalkers” was one of the only three she played in. She committed suicide in 1963. She was unforgettable in the film “Nikt nie woła” by Kazimierz Kutz. Her competitors for the role of Lucyna were Elżbieta Czyżewska and Beata Tyszkiewicz.